12588 PRIVATE CLIFFORD GEORGE HURREN

9TH (SERVICE) BATTALION ESSEX REGIMENT

KILLED IN ACTION

19TH OCTOBER 1915

AGE 19 YEARS

Clifford was one of six pairs of brothers from the town to lose their lives during the Great War (see Amos). He had been born in Halesworth in 1896, the fourth child born to Amos and Eliza (née Spoore). As a young boy he had spent his formative years of study at the town’s boys’ school, where he was best remembered as being one of the four members of the school’s relay swimming team that were victorious at the 1907 local schools swimming regatta by winning the Lady Gooch Challenge Shield. A triumphant article published in the Halesworth Times newspaper of 1st October 1907 described how, although at a considerable disadvantage regarding how the other school teams in the competition were able to carry out their training in the relative comfort of using their local swimming baths, the boys from the town only resource was that of the Blyth river. Reporting on the race, Clifford was highly praised for swimming the final leg, as this was his first competition and he was the youngest and smallest boy in the race. It related that he had entered the water with a short lead over the other teams which he then went on to increase to a winning length of several yards over the second team representing Lowestoft British school.

Some years ago, found in a lot of scrap silver was a small plaque not much bigger than a 50 pence piece that had been originally mounted on the Lady Gooch trophy. Engraved on it were the names of the winning Halesworth team members, being George Carter, Leonard Cole, Ernest Peck and Clifford Hurren (see below). At the time of the presentation in 1907, no one could have foreseen how emotive this small shield would become, for within twelve years three of these four boys would have given their lives in the Great War with the fourth, Ernest Peck, having been discharged from the army due to wounds. Surely there can be no better example of how the “War to End All Wars” would decimate an entire generation of British Manhood.

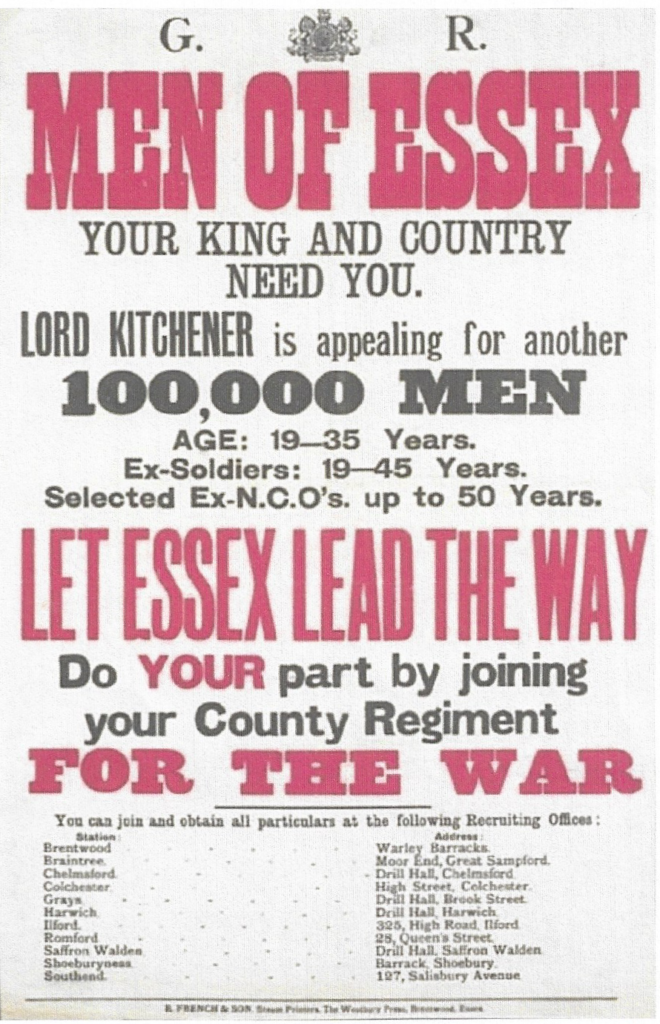

On leaving school in 1910 Clifford found work as a messenger boy employed by the Post Office at their premises in Bridge Street. In the 1911 G.P.O. appointments book he is shown as still living and working in the town, now rated as an assistant postman. At the time of the 1912 edition, he is listed as serving in the main Post Office at Ilford, Essex, now graded as a qualified postman. Shortly after the outbreak of the war in August 1914 and no doubt having been caught up in the excitement and patriotism of that time he joined with many other young men in signing on to enlist in the army, at the recruiting office in the High Road, Ilford (see poster below) to serve as 12588 a Private soldier in the 9th (Service) Battalion, Essex Regiment which had begun to be formed after Lord Kitchener’s appeal for the formation of what he had described as a complete new citizen army. It was originally based at the Essex Regimental Depot situated in Warley Barracks, near to the town of Brentwood. Within a month they were on the move to Hythe in Kent. This was to allow other new battalions the facility of the Depot. At the same time, the 9th Essex joined with other regiments from the east of England in forming the 12th (Eastern) Division, this would include the 7th (Service) Battalions from both the Norfolk and Suffolk Regiments. In March 1915, the whole of the Division gathered in Aldershot before proceeding to France with the 9th Essex landing at Boulogne on the 31st May 1915. On arrival their first few weeks on the Continent were taken up by further training in trench warfare under the direction of experienced troops, before entering the front line in the area of Armentiéres in northern France. Where, over the following few months, they were considered to have had a quiet time, giving them a period to settle into the routine of a battalion at the front.

Although having suffered what at that time was considered a small number of casualties during the summer of 1915, the 12th Division’s true baptism of fire would begin in late September when they were moved to the Loos front, arriving there on the 29th of the month. Here, over the following few days, the 9th Essex took over trenches in the area of the Vermelles Quarries. It was near here that one example of how the war at the front could affect soldiers of all ranks and status, occurred. On 2nd October, while the Divisional Commander, Major General Frederick White, was visiting some of the troops, he was killed by a bursting artillery shell. By 18th October, the day prior to Clifford’s death, his battalion were holding a section of the German trench system within the quarries, with the enemy sheltering in a continuation of the same trench behind barricades. It had been decided that the best method of clearing the Germans out of the line was by the use of bombing squads. These were men serving in every British infantry battalion under their own officer (see George Frost), who had been trained in the handling and use of hand grenades. It had been found that the grenade could be particularly effective within the tight confines of a trench. When clearing dugouts, a rifleman, particularly with his bayonet fixed, would find it hard to manoeuvre and fire his weapon, whereas a well-placed grenade could and very often did wound or kill one or more of the enemy. Whether Clifford had been a member of the Bombers Squad is not known but, as the trenches were cleared, riflemen and machine gunners would then be required to hold the ground won. As the battle within the trenches continued, the German artillery kept up a constant barrage on the sections of the line taken by the men of the 9th Essex. One sad fact that was later related in the battalion’s war diary for 18th and 19th October was that, to counter the German’s artillery barrage, the British gunners began to fire in support of our troops but, due to poor communications, a number of their shells fell short, regrettably killing at least one of the 9th Essex’s officers and an unknown number of soldiers. After last light and right through the hours of darkness the German infantry made several attempts to regain those positions lost during the previous twenty-four hours but with no success as the men from the 12th Division remained firm in holding what they had won. The war diary entry for the 23rd October 1915 shows that on the period between the 12th to the 21st of the month the battalion’s losses in dead and wounded amounted to seven Officers and two hundred and nine Other Ranks. Among these numbers would have been young Clifford, whose body could not be identified. He is therefore remembered on the Loo’s Memorial to the Missing.

As appears to have been a common occurrence right throughout the war, Clifford’s loss had been conveyed to his parents in a letter of condolence from one of his comrades rather than through the official channels which, on many occasions, could take several days, if not weeks. In the letter from his friend, he wrote of their son’s popularity among the men of his Company and the deep regret they felt for his loss, as all of those who knew him had the highest admiration for the courage he had always displayed.

On 18th August 1919, Clifford’s mother Eliza, having been nominated as his next of kin, received the final payment of a gratuity totalling £9.3s.3d (£9.16p) for the loss of her son.

She would also have been able to claim his medal entitlement of the 1915 Star medal trio, his named bronze memorial plaque and scroll.

The location of these is not known.

This may have been a copy of the recruiting poster that encouraged Clifford to sign up.