15272 LANCE CORPORAL LEWIS ALBERT NEWBY

7TH (SERVICE)BATTALION, SUFFOLK REGIMENT

DIED OF INFLUENZA

WHILST A PRISONER OF WAR IN GERMANY

12TH NOVEMBER 1918

AGE 25 YEARS

Another young son of Halesworth who would go on to lose his life in very sad circumstances was Albert Newby who, although having been named Lewis Albert, for all of his short life preferred to be known as Albert. Born in the town during the third quarter of 1893, he was the fourth child of James, a brewer’s cooperman and Martha (née Harper). While attending the Boys School he was described as a young fellow of rare promise with a fine tenor singing voice, which he often put to good use as a member of the United Reformed Church in Quay Street. After schooling, Albert had originally found work as a groom employed by Mr Herbert Broom, an estate agent who lived in the nearby village of Holton, possibly in order to give his growing family, now consisting of nine children, more room in their home at 23 Wissett Road. By the time of the 1911 Census, he was a boarder with a Mrs Canham, also living in Holton.

At the outbreak of war in August 1914, Albert remained in the employ of Mr Broom, who was reported to have held him in very high esteem, but after Lord Kitchener’s famous appeal for young men to form a completely new army, Albert travelled to Ipswich in September to enlist. There, after being declared fit to serve, he was issued with the regimental number of 15272 with the rank of a Private Soldier in one of the new Service (Kitchener’s) Battalions of the Suffolk Regiment. He was originally sent for his basic training to Shorncliffe on the Kent coast. This would have been expected to last six months. However, at that time, things for the Regular soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force now fighting with their French and Belgian allies on the Western Front, were not going so well, with them eventually becoming involved in what became known as the retreat from Mons. It was during this confused fighting that the 2nd Battalion Suffolk Regiment arrived on the Continent, having travelled from their home base at the Curragh in Ireland. On landing at Le Havre on 17th August 1914 they pushed forward into Belgium where on 26th August, they became involved in the battle of Le Cateall. Here, after a few days, they were forced to retire, having experienced enormous losses. Out of a force of nine hundred and ninety Officers and men the 2nd Suffolks had suffered the loss of eight hundred and eighty-six all ranks. After this disaster the remnants of the Battalion were withdrawn back across the French border to rebuild and re-equip. During the next few months, with the majority of the Regular Army now needing to be reinforced, it was not long before the part-time soldiers of the Territorial Force were being despatched to bolster the B.E.F. and its shortfalls in their order of battle. These Territorial battalions were quickly followed in the new year by partly trained men who, just months before, had enlisted into Kitchener’s new army battalions now being sent out to join what remained of several of the regular battalions as casualty replacements. This is how Albert, with a little over four months training, came to be posted to join the 2nd Suffolks in France on 26th January 1915. How long he remained with the battalion is not known but at some point he had been transferred to join the 7th (Service) Suffolks who after being confirmed as ‘Fit to Fight’ had crossed over to France at the end of May 1915. It may have been now, after gaining front-line experience with the 2nd Suffolks, that he received promotion to the rank of Lance Corporal. On 4th April 1916 Albert, who had now been on the Continent for some fifteen months, wrote a lighthearted letter to one of his brothers in which he thanked him for a gift of the ‘Fags’ that he had received, explaining that they had ‘smoked beautifully’. He then went on to mention that he had recently met up with some of their Halesworth chums, one being Albert Grice who was serving with the Royal Garrison Artillery and who would later go on to be killed (see his story); also several of the lads who were serving with the Halesworth Territorials from the 4th Suffolks, who at that time had been located close to him and his battalion. He went on to enquire about the Zeppelin raids on East Anglia. By the middle months of 1916 the war on the Western Front, which was now in place from the French coast to the border with Switzerland, had virtually ground to a halt, with very little action being taken by either side, apart from the odd trench raids to gain information. The allies now decided it was the right time to mount a major offensive in the hope of making a breakthrough in the Somme region of northern France. The assault was to be made by the British Fourth Army on the left and the French Sixth Army on the right, over a twenty-five mile section of the German front line. This battle would go down in history as the Battle of the Somme and would last from 1st July until 18th November 1916. Albert and his comrades in the 7th Suffolks, as part of the 12th Eastern Division, were not committed in the early phase but were held in reserve, receiving orders to move into the support trenches during 2nd July in preparation for them to attack the village of Ovillers the following day, with zero hour set at 3.15am. On studying the 7th Suffolk’s war diary for that day, it appears that Albert was serving in the machine-gun section of his battalion’s ‘C’ company. They were to lead the attack with ‘D’ company, while their ‘A’ and ‘B’ companies followed up. Exactly on time the leading companies advanced with the 5th Royal Berkshires on their right. As they went forward, they received a covering bombardment laid on by their own artillery. At first the leading elements progressed very well with the Suffolks taking the Germans’ first and second lines of defence, but as they advanced, due to the darkness of the night and the heavy weight of fire now coming from the enemy’s rear, they and the Royal Berks lines had begun to drift apart. This then allowed the German infantry, who were always able to exploit any advantage, to infiltrate the gap between both of the battalions and then cut off the troops forming the first line of attack and those following up. These troops were then driven back to their own line. Now unable to advance without support or withdraw through the enemy troops behind them, the remnants of the two leading companies, already greatly reduced in numbers, were forced to surrender. Later that day, after the 7th Suffolks’ headquarters staff had managed to compile their numbers, it was found that the total number of casualties killed, wounded and missing amounted to twenty-one Officers, including another Halesworth casualty 2Lt Robert Frost (see his story). All of the four Company Commanders had been killed with four hundred and fifty-eight Other Ranks. Albert was one of those forced to surrender.

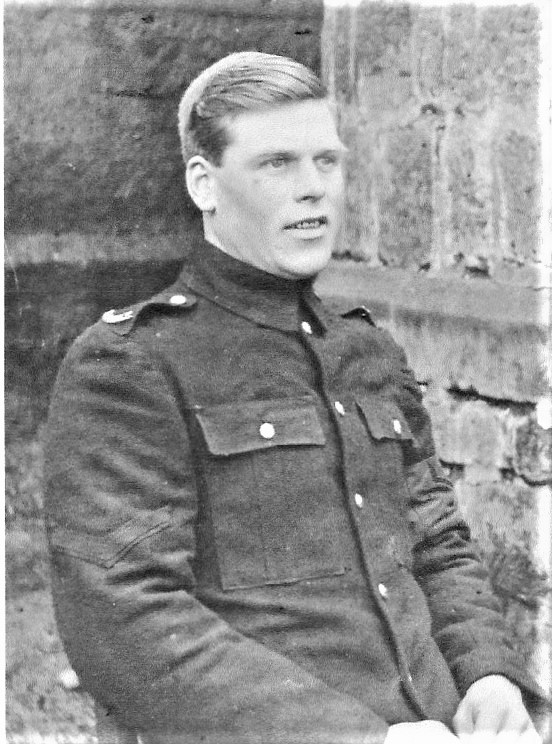

It has not been recorded how the British prisoners were treated after their capture, but six weeks later Albert and several others from his battalion had been interned in the Sennelager camp, situated in the German region of Westphalia, where they would remain up to the war’s end and beyond. On the 5th May 1918, in a letter to his sister-in-law Cissy which accompanied the photograph of him above, showing that, although he had been a prisoner now for almost two years, Albert still managed to maintain a soldierly appearance with his brass buttons and shoulder titles kept clean and polished, although, as was the practice with the Germans, his khaki tunic and trousers had been dyed black. In his letter he mentioned that he had received a letter from his older brother Jim who, during that period of the war, was serving with the Army Service Corps in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) (see below). The letter had taken some four months to reach him. As the Great War was finally coming to an end in November 1918, the world had been suffering for several months from a pandemic commonly known as the Spanish Flu which officially lasted from February 1918 until April 1920. This had affected every country and could not have appeared at a more critical time for the population of Europe, particularly the inmates of prison camps in Germany who for months had been underfed and poorly treated, due to the food shortages that the Germans were experiencing. Sadly, on 12th November 1918, Albert passed away from the virus, just one day after the Armistice had been signed. On his death he was laid to rest in the Niederzwehren Military Cemetery, Kassel, Germany, where he lies today with one thousand, eight hundred other British and Commonwealth casualties from both World Wars.

It would have been a few weeks later that his parents heard the sad news of Albert’s death. An article recording his loss, printed in the Halesworth Times of 31st December 1918, it reported that they had received a letter written by him on the 2nd November in which he had stated that he was in the best of health and was hoping for the war to end soon so that he could get back to Halesworth and home, only for him to die ten days later.

On 15th July 1919 Albert’s mother Martha, having been listed as his next of kin, received a war gratuity totalling £74.8s.3d (£74.41p) for the loss of her son. This large amount, compared with what some other relatives had received, was no doubt due to his spending so long as a prisoner without drawing any pay. Just prior to this payment, on 7th July, Martha had notification that she had also been awarded a Dependents Pension of 5s 0d (25p) a week, which, on her death in April 1926, passed on Albert’s father, James.

As well as the monetary awards his parents would have been entitled to claim his medal awards of the 1915 Star trio with named memorial plaque and scroll.

This a copy of a memorial card, the family had printed to announce their loss.

This photograph is of Albert’s brother Jim while stationed in Iraq serving in the Army Service Corps