43044 PRIVATE BERTIE CROFT

7TH (SERVICE) BATTALION SUFFOLK REGIMENT

DIED 23RD APRIL 1918

(FROM WOUNDS RECEIVED 28TH APRIL 1917)

AGE 22 YEARS

The early years of Bertie’s life have been difficult to trace, but we know he was born to Ellen Croft, possibly illegitimately, on the 22nd October 1895. Ellen herself had been born in Bermondsey, South London, in 1875. Sixteen years later at the time of the 1891 census, her entry shows that she was in the employ of a Mr Ripps Massingham, a butcher and farmer of the Thoroughfare, Halesworth, where her duties consisted of being a General Servant and Nanny to the family’s five children. Who fathered Bertie and what name his birth had been registered under remains a mystery, although it appears that Ripps and his wife Elizabeth must have stood by her after Bertie’s birth since she remained in their employment up until the 1901 census, when she is listed as living and working for the family at their premises, No.1 Thoroughfare, although there is no sign of Bertie. In 1905 Ripps died. Shortly after his death Ellen married Ernest Spoore, a brewers drayman in the first quarter of 1906. She then moved into his home at 76 London Road. At the time of the 1911 census Bertie appears to have eventually appeared on official records, since a lad of his name and age is listed as a house boy, resident in the Walberswick Cottage Home for invalided and crippled boys, with at least one described as being feeble-minded, their ages ranging from seven to fifteen years of age.

As the seaside village of Walberswick lies just eight miles to the east of Halesworth, this might be Ellen’s son, although, as a further twist in this particular tale, on this census his place of birth is shown as Manchester. However, a search of the birth records for that period and location shows no sign of a boy of that name having been born there.

Unlike the majority of all British fatal casualties of the Great War, Bertie’s service papers survive. These, combined with other sources of research, enable the researcher to produce a fairly accurate pen-picture of the trials and tribulations of his life in khaki up until the time of his death. On the 1st October 1914 he set out from his then home in the village of Hacheston, which is situated close to the town of Wickham Market, to travel the not inconsiderable distance for those times of some twenty-seven miles to the town of Beccles, on the Suffolk/Norfolk border, in order to enlist in the town’s Territorials of the 6th (Cyclist) Battalion, Suffolk Regiment T.F. Why he made this journey when he could have signed up in any of the towns close to his home is not clear. Furthermore he would have had to pass close to Halesworth where he could have enlisted while visiting his mother. One possible answer could be that he may have been a keen cyclist with his own bicycle and would have been happy to join a Cyclist Battalion with like-minded volunteers. After passing the necessary medical examination and documentation he was enlisted to serve as a Private Soldier with the regimental number of 1764. This would have changed after 1917 when members of the Territorial Force were brought into line with the rest of the army, with Bertie receiving the new number of 43044. His personal details as entered on his enlistment papers stated that he was nineteen years of age, that he was 5 ft 6 ins tall and had a chest measurement of 35 inches. His trade or calling is listed as being a general labourer with a later entry showing him as being a horse dealer. For his next of kin he nominated his stepfather, Ernest, and his mother, Ellen, now living at Bramfield Hill near Halesworth.

After carrying out ten days’ basic training in the Beccles drill hall, Bertie, along with others from his intake, were transferred to the Suffolk town of Leiston where they were found accommodation in and around the works of Richard Garrett and Sons, manufacturers of steam traction engines. While there, it was decided to form a second battalion of cyclists with the original Territorials and new recruits split between the two new units, now known as the 1st/6th and 2nd/6th (Cyclist) Battalion, Suffolk Regiment. Both of these units were to remain in England employed in the Home Defence role since being cyclists, they were able to patrol large areas of the eastern counties coastline where it was believed any invading forces would land. Bertie was posted to join the 2nd/6th Battalion, who after a short time, were relocated to be based in and around the town of Louth near the Lincolnshire coast.

Over the next few months Bertie would have completed his training and been posted to serve in one of his Battalion’s four companies. Each of them were now stationed at various points between Skegness and Sutton-on-Sea to carry out their patrols. Within the local population it was reported that the people of Lincolnshire really grew fond of the sturdy men from Suffolk, which lead to several romances.

As the war progressed and the number of casualties mounted to many hundreds of thousands, men of the right age groups were asked if they were prepared to serve overseas. It appears that Bertie volunteered with many of his comrades of the 2nd/6th. Their time came shortly after the opening phase of the battle of the Somme with the massive losses inflicted during the first week in July 1916. By mid-July Bertie had joined a draft of men from the 2/6th Suffolks who were transported by train to Folkestone on the Kent coast. From there they sailed to France, landing at Boulogne on the 26th July. After a short time spent at a reinforcement centre, he and several of his comrades were posted to join the 7th (Service) Battalion Suffolk Regiment on the 12th August 1916. His new battalion had been formed at Bury St Edmunds in August 1914 after Lord Kitchener’s appeal for young men to enlist in a totally New Army. After training they had crossed to France in May 1915. The Battalion had taken part in the opening few days of the Somme offensive, suffering four hundred and eighty casualties on the 3rd July alone. By the time that the reinforcements joined them in the area of Bouzing Court they had just been once again relieved from the firing line and desperately needed a large number of casualty replacements. Initially posted to ‘A’ Company Bertie began his eleven months of service with the 7th Suffolks, during which time he quickly learnt that the life of a front-line infantryman was a total change from that of a military cyclist patrolling the coastline of Lincolnshire.

At 4.28am on the 28thApril 1917 Bertie, with his battalion, left their trenches situated to the front of the village of Pelves in the Arras sector. Their role that morning was to support an attack on the German front line with the 7th Norfolk Regiment and the 5th Royal Berkshires in the vanguard of the assault, the plan being that when the two forward battalions began to take casualties, the Suffolks could then pass through them to continue the advance and, it was hoped to enter the enemy’s line. Right from the start, the Germans were alert to the troop movements and began to pour machine gun fire into the advancing Tommies. This was also backed up by very heavy fire from the enemy’s artillery. Poor Bertie was caught in the barrage, suffering severe shrapnel wounds to his abdomen and back. Luckily for him he was picked up by his Battalion’s stretcher-bearers and carried to the rear where he would then have entered the evacuation chain that finally found him as a patient in the Stockport Military hospital in the north-west of England. Here he underwent major surgery. This caused him to stay in hospital recuperating for the next ten months.

On his release from the hospital he was medically assessed and was declared to be unfit for any further military service due to wounds. He was then discharged from the army, having served a total of three years and one hundred and two days. On the 10th January 1918, due to the nature of his discharge being honourable, he was awarded a Silver War Badge. These had been issued to men who had qualified from the 12th September 1916, in order that the men wearing the badge and not in uniform would not be harassed for not doing their duty. Each badge bore a number to prove it had been issued to the individual concerned. Bertie was number 300690. As with many other discharged ex members of the military, he was found work to help the war effort, although because of his injuries, he was not able to undertake heavy activities. After training he was appointed as an inspector at the Chilwell National Artillery Shell Filling Factory, that was situated in Nottinghamshire.

From a report written in the Halesworth Times newspaper of the 21st May 1918, recording Bertie’s death, it seems that barely after three months of being employed in his new role the strain of the work was too much for him and his death followed after a few days of illness at the young age of twenty-two years. The article goes on to describe his funeral with full military honours, with him being laid to rest at St Michaels Church, Brumcote, Nottinghamshire on the 2nd May 1918.

The chief mourners present were his mother, Mrs Ellen Croft, (why she was listed under her maiden name is not known) and Bertie’s fiancée, Miss Elaine Clarke. Where they had met and become engaged to be married remains a further mystery. Today Bertie’s grave, complete with military headstone, remains one of three in the churchyard maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

After his death, his mother, as his next of kin, received a weekly pension of 3s 6d (18p) rising to 5s 0d (25p) after November 1918. This was followed by a gratuity of £15.0s.0d (£15.00p) awarded in February 1920. She would also have been entitled to receive his medals which consisted of the British War and Victory medal pair with his named memorial plaque and scroll.

The location of these is unknown.

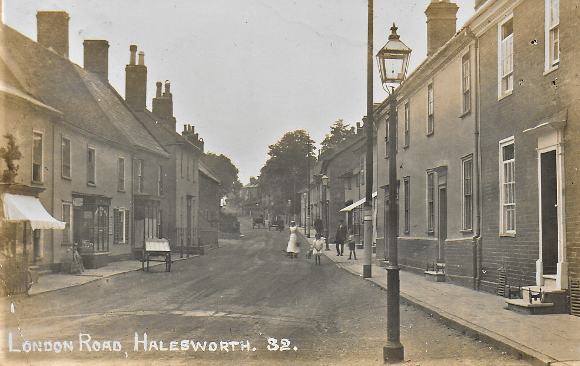

Postcard of London Road, Halesworth 1916

Where Bertie’s mother was living