An article that did not make the press this month

Back to school

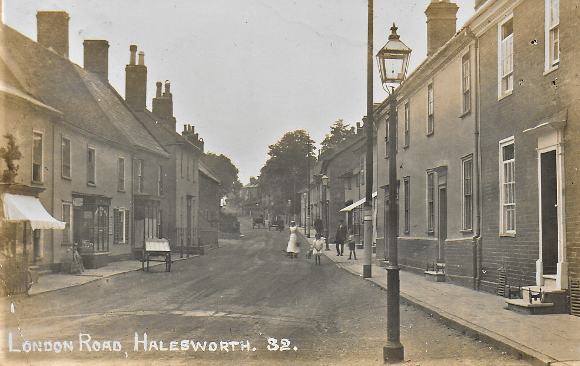

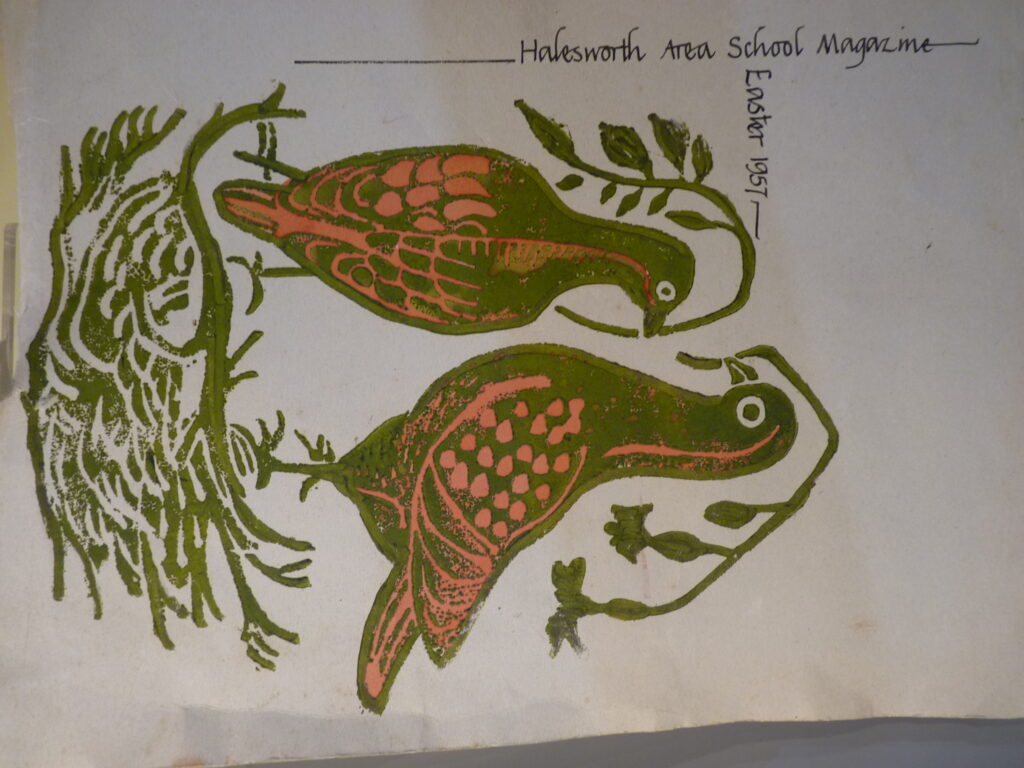

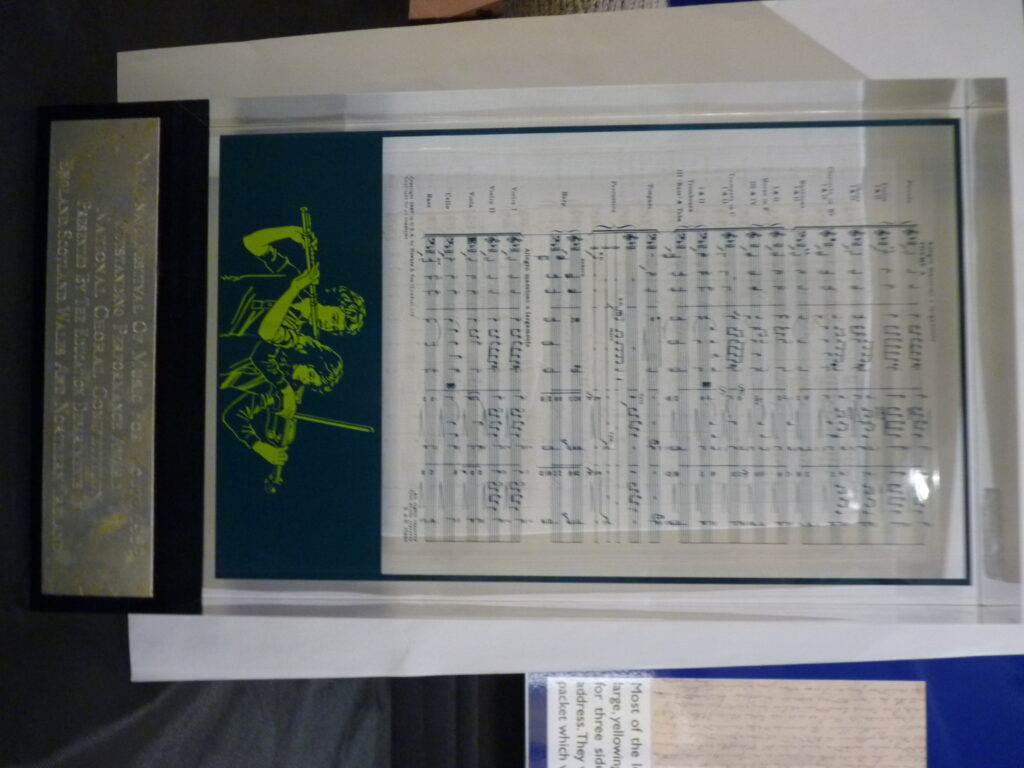

If you would like to jog your memory of the old Halesworth Middle School and Secondary Modern School, Halesworth & District Museum is the place to go. Photos, sports cups, school magazines and a national award for choral singing are just some of the memorabilia in a brand-new display featuring the town’s former schools. Even if you hated your old uniform, you might be tempted to have another look at those old school ties, jumpers etc. There is also a chance to pick up the Middle School bell and give it a ring for old times’ sake.

From 1923 to 1958, Halesworth children aged 5–15 attended the Halesworth Area School, at the site which is now Edgar Sewter Primary School. Those who passed the 11-plus exam had the opportunity to continue their education at Bungay or Beccles, and the rest left school and generally entered the work force.

In 1958, Halesworth Secondary Modern School opened its doors to 11–15-years-olds, on a site facing the Norwich Road. The former Halesworth Area School became Edgar Sewter Primary School, for children aged 5–11. As before, those who passed the 11-plus could go on to Bungay or Beccles.

In the 1970s, Suffolk introduced a three-tier system of education. In Halesworth, this meant children left Edgar Sewter Primary School at age 9, and moved to Halesworth Middle School – on the premises of the former Secondary Modern. At age 13, they transferred to high school in Bungay or Beccles without sitting an 11-plus exam.

Then in 2010, Suffolk reverted to a two-tier system. Edgar Sewter incorporated two extra year groups, so children could stay until they were 11, then their education moved out of Halesworth when they transferred to high school. Halesworth Middle School closed in 2012.

So, whether you were a schoolchild, a parent or indeed both during these years of educational change, why not come and jog your memories at the Museum? There will also be a reunion at the end of this month, so do book a place.

Schools Reunion Evening

Who is invited?

Former pupils of Halesworth Area School, Halesworth Middle School and Halesworth Secondary Modern School, and/or their parents

When is it?

Thursday 27 April, 6–8pm

Where is it?

Halesworth & District Museum

What does it cost?

It’s free, and there will be refreshments

Should I book a place?

Yes. Please email the Museum at office@halesworthmuseum.org.uk, using ‘Reunion’ as the title of your message

Floods past and future

A very different kind of memory will be evoked by another new display. In collaboration with the Ink Festival, Halesworth & District Museum is staging a multimedia focus on flooding – a perennial threat to those of us living in coastal East Anglia.

The Rising Waters display, opening this month, commemorates the disastrous events of 31 January 1953, when the worst floods in recorded history hit the east coast of Britain.

There was no warning, and people had little or no chance to escape from the relentless inundation. The cost, in both human and financial terms, was huge. Along the coasts of Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex, 307 people died. Farmers in East Anglia lost around 46,000 head of livestock. Nationally, more than 30,000 people were forced from their homes and almost 1,000 miles of coastline was seriously damaged.

Although many inland communities were devasted as the tide rushed across the land, Halesworth itself was not flooded on this occasion. Two Halesworth police officers joined the rescue efforts in Southwold and Walberswick. And local volunteers stepped forward to help with the massive clean-up. In Southwold, the worst of the damage was on Ferry Road, where a tidal wave swept along the River Blyth, destroying homes in its path. Five people in the town were killed – a mother and baby and three elderly women.

Before and after 1953, Halesworth has seen its share of flooding, albeit on a far less devastating scale. Many will remember the incongruous sight of people boating along The Thoroughfare, and the plight of traders trying to save their stock.

And, as the Rising Waters display points out, there are important questions to ask about the future, with the evidence of rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and sometimes bizarre weather conditions. More people live in our region now than in 1953. There are more houses near our coast, and the roads carry far more traffic.

It is now 70 years since the terrible of floods of 1953. How would we cope if they happened again?