SECOND LIEUTENANT ROBERT WALL FROST

7TH (SERVICE) BATTALION, SUFFOLK REGIMENT

MISSING IN ACTION

3RD JULY 1916

AGE 26 YEARS

Like his younger brother George (see George Jessie), Robert had been born to William and Mary at Romford, Essex on the 22nd February 1890. After completing his education at the Mauney Road Boys School he followed his father into the retail profession, where by the time of the 1911 census he could be found employed as an assistant to an ironmonger, while boarding with his brother George in a private house at Ilford, Essex. In 1913 he had moved somewhat upmarket, now employed as a draper while living in Grosvenor Street in London’s wealthy district of Mayfair.

On the 8th January 1913 Robert began his military service when he enlisted to serve as 1509 a rifleman in the 16th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Queens Westminster Rifles), Territorial Force. Originally formed in 1908 the T.F. had units based the length and breadth of the British Isles. On their formation, their original terms of service were one of purely home defence; however, by 1910, with the possible outbreak of a major war at some time in the near future, members of the force were encouraged to sign the Imperial Service Obligation under which they pledged that in the event of a national crisis they were willing to serve overseas in support of the Regular Army. Within the Territorial Force the London Regiment was by far the largest, consisting of twenty-eight Infantry Battalions with many of them maintaining links to their predecessors, the Old Volunteer Rifle Corps from which they had originated; hence the Queen’s Westminsters being included in their title. Other examples included the 8th Battalion (Post Office Rifles) and the 28th Battalion (Artists Rifles).

On his enlistment documents, Robert had nominated his father William now residing at No.8 Thoroughfare, Halesworth, as his next of kin. They also show that he attended his first ten-day annual training camp from the 3rd August 1913 when, in company with the rest of his comrades, he travelled to Abergavenny in South Wales. After his return he continued to train during drill nights and at weekend training sessions. This all changed on the 5th August 1914 when he, along with the entire Territorial Force, were embodied to serve full-time, after the British Government’s declaration of war against the Kaiser’s Germany. On being mobilised the Queen’s Westminsters then left the city, travelling to Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire. While there the Battalion’s title changed to that of the 1st/16th Westminsters with a newly formed sister Battalion becoming the 2nd/16th. This was to be manned by those men who had not signed the Imperial Service pledge, with others returning who had recently been discharged as well as new recruits. While in Hertfordshire they would have then begun a period of intensive training in preparation for ultimately taking their place at the front. This was to come much sooner than any of them at that time could imagine.

During the early months of the war the British Expeditionary Force that eventually consisted of two Cavalry and seven Infantry Divisions of regular army troops had, with their Belgium and French allies, fought hard to stem the advance of the German forces as they stormed through Belgium and into Northern France, but in doing so the cost in the number of casualties suffered by the British army had been very high. Research shows that by the end of November 1914 in excess of eighty-eight thousand Officers and Other Ranks had been killed, wounded or missing. It was now that the previously much maligned Territorials or, in the language of the day, Saturday night soldiers, stepped forward, with Robert and his comrades of the Queen’s Westminsters crossing to France on the 3rd November where, over the following few days, they were joined by numerous other part-time Battalions including Halesworth’s own ‘F’ Company of the 4th Suffolks. While other Territorial units were despatched to far-away outposts of the British Empire to replace regular troops, who were then enabled to join those forces in France and Flanders.

It was later declared by the then British Commander-In-Chief, Sir John French, that “Without the assistance which the Territorials afforded between October 1914 and June 1915 it would have been impossible to have held the line in France and Belgium or to have prevented the enemy from reaching his goal of the Channel Seaboard”.

With that statement the Territorial soldiers had proved their most ardent critics and detractors wrong, including one of the most famous, Field Marshall Lord Kitchener.

Within a short time of their arrival, the Westminsters had joined the Regular 18th Brigade of the 6th Division, then holding positions in the area of the Flemish town of Ypres. Here they settled down to learn the art of trench warfare. During the course of the next few months all appears to have gone well for Robert and his chums as they adjusted to life at the front. On the 1st March 1915 he received his first promotion to that of a Lance Corporal. DurIng July 1915 the Westminsters had become involved in the major battle of Hooge after which they were awarded their first Battle Honour. It was during this action, fought between the 19th to the 30th of the month that Robert suffered a gunshot wound to his thigh. After receiving treatment at the 18th Field Ambulance, he was eventually returned to an Emergency War Hospital in England where he remained until late September. On his release from hospital and possibly after a period of leave with his parents in Halesworth, he received orders to report to the 3rd/16th (Reserve) Battalion of his regiment who at that time were based in Richmond Park to the west of London. It was while there that he had applied to be considered to be granted a King’s Commission. After various interviews he was sent to the Officers’ School of Instruction at Connaught Barracks, Dover. On the 3rd November 1915 he was gazetted as a Temporary Second Lieutenant, requesting that he be posted to his brother’s old 7th (Service) Battalion, Suffolk Regiment with whom George had lost his life just two months previously. Prior to joining them in France he was sent to join the 10th (Reserve) Battalion of the Suffolks who were at that time based at the Regimental Depot in Bury St Edmunds. Here among other subjects, newly commissioned Officers were trained in the art of leadership and minor tactics. A further four months would pass before Robert joined a draft of officers being sent out to join their Battalions a week before Easter 1916.

Studying the 7th Suffolks’ war diaries for April, May and June, it appears that, apart from the odd period spent in the front line, a great deal of time was dedicated to training, with much emphasis placed on the attack and consolidating captured enemy positions. Sadly the reason for this would soon become apparent when, on the 1st July 1916, the opening phase of the Battle of the Somme began. This would prove to be the single most costly day in lives lost ever suffered by the British Army. The 7th Suffolks on that day were in the reserve line in the area of Franvillers before moving forward to Heincourt on the 2nd July, where they then occupied the support trenches. It was while there they received orders to prepare to make a frontal attack on the village of Olvillers. This was to commence at 3.15 am on the following morning of the 3rd July. Robert was now commanding a platoon in ‘D’ Company which had been tasked to lead the attack to the right of the Battalion’s frontage, with ‘C’ Company to their left and the other two companies in support. At the allotted time and under a Royal Artillery creeping barrage, that had commenced ten minutes prior, the men of the 7th Suffolks went “over the top”. The initial phase of the attack proceeded very well. Within a short time they had advanced over the Germans’ front line and were in the outskirts of the village itself. Regrettably the Battalion to the Suffolks’ right, the 5th Royal Berkshires, had lost touch with ‘D’ Company owing to the darkness of the night. This then enabled pockets of the enemy to outflank Robert and his Company and to get between them and the following troops of the second wave.

Now isolated, the order to withdraw was given to the men of ‘C’ and ‘D’ companies, then having to engage the enemy to the front and rear. It would have been during this very confused fighting that Robert was last seen. Later that day the remnants of the 7th Suffolks were back in their own support line where, after a roll call, it was found that a total of twenty-one Officers and four hundred and fifty-eight Other Ranks were recorded as having been killed, wounded or posted as missing, with Robert being listed in the third group.

At Halesworth the news of Robert being missing in action was conveyed to his parents in a telegram delivered to them on the 7th July followed by a short article published in the Halesworth Times newspaper on the 1st August 1916. Having been classified as missing in action, his father William then began writing a series of letters in the hope of trying to confirm whether his son had been killed or perhaps had been made a prisoner of war. Copies of these letters and replies were found in Robert’s service records held at the National Archives at Kew. In one William had contacted the headquarters of the International Red Cross in Geneva, Switzerland who were acting for all the nations involved in the conflict by trying to locate men who had been made prisoners. Another source of information at this period of the war could be the American Embassy in Berlin who had, prior to their declaring war against Germany in April 1917, been acting as intermediaries on Britain’s behalf. Regrettably none of his enquiries could confirm what had happened to Robert.

Eventually a statement was received from a member of Robert’s platoon, 13160 L/Cpl George Seaman who hailed from the village of Brockdish on the Norfolk Suffolk border. He stated:

“That during the attack of the 3rd July 1916 at one point I was about four yards from my platoon officer, Mr Frost, when I witnessed him fall presumably hit by a bullet. Later after he himself had been wounded and whilst crawling back to our lines he had seen Robert lying face down near a shell hole and he could not see any movement. Although dawn was just breaking, he could identify his officer by the equipment he was wearing by the light of star shells that were being fired by both sides.”

On the 17th July 1917, just over a year after Robert had been listed as missing in action, the town’s newspaper reported that Mr and Mrs Frost had received from Buckingham Palace a letter of sympathy confirming Robert’s death, although his remains were never found. Today he is remembered on the Thiepval Memorial to the missing which bears the names of seventy-two thousand, three hundred and thirty-seven men with no known grave who were reported as being lost during the Somme battles.

On the settling of his son’s accounts in December 1917 William had received a total sum of £43.6s.3d (£43.31p). He and Mary would have also been able to claim his medal entitlement of a 1914 Star, named to Robert as a Private soldier in the 1st/16th London Regiment and a British War and Victory medal pair inscribed with his rank of Second Lieutenant, plus his named Memorial Plaque and Scroll.

The location of these awards is unknown.

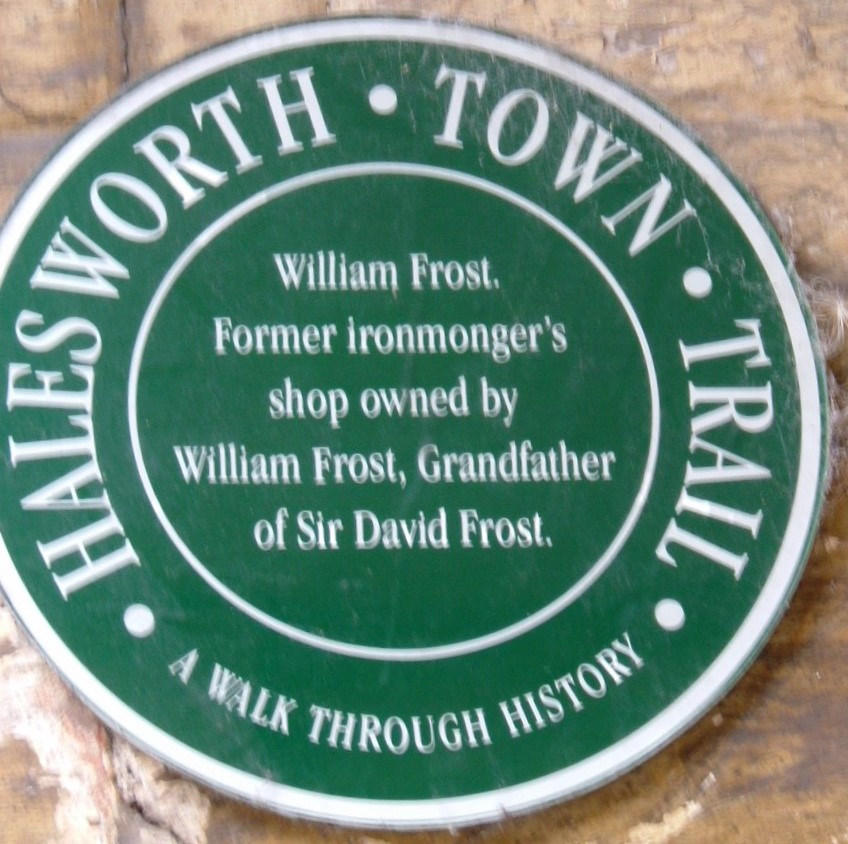

Apart from the two brothers, there were two further siblings, an elder sister, Mabel, and a younger brother Wilfred, who had been born at Romford in 1900. He had been conscripted into the army in May 1918 to serve as a Rifleman in the 51st (Graduate) Battalion, Rifle Brigade, then based as a training battalion at Ipswich. Fortunately for his parents, having lost two sons, the war ended before young Wilfred would have been sent to the front line. In 1922 he married Maud Aldrich from the nearby village of Darsham. They then went on to have three children, the youngest being a boy named David (1939-2013) who, after attending university, went on to become one of the most famous British television personalities of the second half of the 20th and early 21st centuries. In 1993 he was made a Knight of the Realm by Queen Elizabeth. Sir David Frost’s association with Halesworth is remembered today on a named plaque to the side of his grandfather’s old ironmonger’s shop in the town’s Thoroughfare, which is part of the Halesworth Town Trial.